James Cary and Dave Cohen, two very fine comedy writers, recently invited me round to their podcast, Sitcom Geeks, and let me bunny on about Ever Decreasing Circles.

Amazingly, no-one has yet complained.

You can find it via all the usual podplaces, and it's also here.

Ever Decreasing Circles

Thursday, 7 September 2017

Monday, 22 May 2017

A Degree Of Acidity

I’m not the only one asking questions about Ever Decreasing

Circles.

In March last year, the series was a specialist subject on fun

TV interrogation Mastermind for contestant Dave Horan.

What’s the name of the suave hairdressing

salon owner who moves in next door to pedantic Martin Bryce and his

long-suffering wife Ann?

Paul. Too easy. Way too easy.

What traditional party game does Martin

play in his garden with the old ladies he’s invited from the retirement home

for afternoon tea?

Harder. Charades. Correct.

Which actor plays Ann and Martin’s

long-standing friend and neighbour Howard Hughes?

Again, easy. Stanley Lebor.

What dish does Martin plan to cook for

himself on the first evening that his wife Ann is in hospital for surgery on

her shoulder? He ends up buying fish and chips because he’s forgotten to soak

the kidney beans.

Detailed, but weighed down by a bloody huge clue: kidney beans.

Name a dish that includes kidney beans. Chilli con carne? Correct.

What is the abbreviated name of the Open

University campaign against government cuts that Ann is involved in? Martin

disapproves and accuses her of becoming ‘a pawn of the Kremlin’.

Now we’re fully into specialist subject territory. I didn’t get this, despite the

second tow-hook clue labouring behind the question. Nor did Dave. It’s OUSA.

Arguably, this is the most esoteric question of the lot.

What is the name of supposedly fierce dog

that a landowner uses to scare Martin, Howard and Hilda away from what they

believe is a public footpath?

Dave passed on this. So did I. No idea. Though, because it’s

Esmonde and Larbey (and mainly because it’s comedy), it’s going to be the most

unassumingly pacifist name, isn’t it? Daffodil or Cuddles or something. Yes, it

is. Blossom. Dave and I both failed this one.

Which two opposing historical groups are

represented in the mock battle at the charity fête? The event culminates in

single combat between Paul and Martin.

(What is it with this construction that dumps a clue after the

question? Third time now.) Slightly too easy. ‘Which two opposingly historical

groups?’ (crap grammar) has ‘Roundheads and Cavaliers’ written all over it. And that's

correct. The Battle of Naseby: the last episode of the third series.

After Paul announces that he needs to move

away for business reasons, possibly to the Channel Islands, what show tune does

Martin happily sing while doing the washing up?

Another sod (and Dave’s second pass): the answer is Oh, What

A Beautiful Mornin’ from Oklahoma! by the peerless Rodgers and

Hammerstein.

What is the full name of the psychiatrist

who Martin meets at Paul’s Party? Ann suggests Martin should visit him professionally.

Proper hard (and fourth iteration of that clue-after-the-question construction). Dave Wilson. (Nice, bland name: nice, bland

character. Very Esmonde and Larbey.)

On Howard and Hilda’s first night on

Neighbourhood Watch Patrol, they arrest a burglar who pretends to be a plain

clothes policeman. Of what rank?

Another toughie, though a guess within reach: Inspector.

Correct.

Some questions reassuringly easy; some quite tough. Retired

teacher David Horan chalked up a very creditable eight points.

And Mastermind wasn’t alone.

Twelve months later – this March – I was alerted to the fiendishly

difficult Listener Crossword in The Times – puzzle 4441, ‘It’s Dark Up Here’.

If you’re not familiar with The Listener Crossword, my trying

to explain it will lose you hook, line and concrete wellies. The potted version

is: it’s properly SEND HELP difficult. So let’s assume you either

know it, or can’t get anywhere near it. (I’m in the latter category, though

with Honours for Bloody Well Trying to be in the former.) Exhibit 1A is clue

1A:

A degree of acidity (to such a degree a

taste of tannin is lacking) is a symptom of thrush.

Well now: here’s how this one pans out – according to Alan

Connor, crossword maven and author of the bloody marvellous The Joy Of Quiz.

A (= A)

degree of acidity (= pH)

to such a degree (= that)

a taste of tannin is lacking (= tannin’s

first letter, so lose a ‘t’ from ‘that’ = ‘tha’)

is a symptom of thrush (definition:

aphtha, ‘the disease thrush,’ says Chambers)

A + ph + tha. Piece of cake, eh? (Me neither.)

Around the perimeter of the crossword are the names

MARTIN, ANN, PAUL, HOWARD and, in the circled lights, HILDA. The complete set.

And circling around the middle are EVER DECREASING OOOOOO and OOZLUM BIRD (look

it up), in ever decreasing circles.

The setter, ‘Colleague,’ explains his thinking behind this

wonderful puzzle here. I shan’t add anything to it, except to

say that it is a work of art.

*

* *

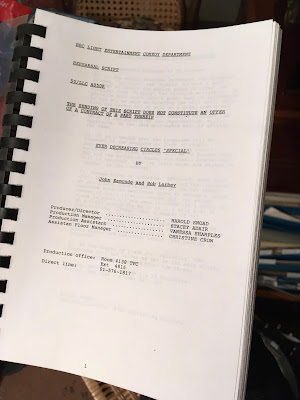

A little extra news: when I met Bob Larbey for lunch in

December 2010 (see Lunch With Bob Larbey), he told me

he hadn’t kept a page of anything he’d written. There were many things I

assumed no longer existed – scripts, paperwork, paraphernalia.

This turns out to have been wrong.

I’ll be writing more about this.

Unusually generous props to David Tyler and John Finnemore for alerting me to the crossword, Alan Connor for scraping my brain off the floor and spooning it back in to my gibbering skull – and to Roger Phillips and ‘Colleague’ (who prefers this styling) for their generosity in helping me assemble this post. Plus knightable mentions to Ian Greaves, Matt Larbey and Eryl Jones. Grats, amigos.

Tuesday, 27 October 2015

The Other One

What follows is a lie.

Here is some dialogue that was cut from Ever Decreasing Circles:

MARTIN: Look, Howard,

I am trying to scull here. Would you kindly stop dragging the anchor in the

water?

HOWARD: Sculls don’t

have anchors.

MARTIN: Now, let’s

have a look at you, Devizes. You’ve put old Bridport in the shade.

HOWARD: Martin, you

are talking to those bits of paper.

MARTIN: You know, I

used to do this for my Auntie Alice. She was a very nice lady. She made a

lovely chocolate spread, I seem to remember. I often wonder if I was

responsible for her phlebitis.

These lines aren’t from Ever

Decreasing Circles. But they easily could

have been.

Before the success of Brush

Strokes (1986-1991), Esmonde and Larbey’s two biggest BBC series were The Good Life (1975-1978) and Ever Decreasing Circles (1984-89). Both

starred Richard Briers, and there’s a clear line to be traced from Tom Good to

Martin Bryce.

As The Good Life begins, Tom Good is a frustrated industrial

designer, turning forty and wondering what more there is to life. His solution

is to apply his skills and enthusiasm to something new: self-sufficiency. Four

series later, he has morphed into a forthright bully, not listening to his wife

or (pretty much) anyone else, and going largely unchallenged. Neither the

writers nor the actor liked the character.

Ever Decreasing Circles introduces a man who tries to control everything, doesn’t listen,

and has gone unchallenged for rather too long. But now – unlike Tom Good – he

has an antagonist, and the two are a mere driveway apart.

Between these two sitcoms there was another, penned by Esmonde and

Larbey for the BBC and starring Richard Briers. And it wasn’t a success.

The Other One has slightly

faded from view. There were two series, in 1977 and 1979. The first was

released on DVD in 2007 to little fanfare, and the second is yet to be

commercially available. It is that rare confection: a sitcom that’s neither

domestic nor workplace.

Ralph

Tanner (Richard Briers) is ‘the most bumptious, pushy, ghastly man in the world’.

At an airport bar, he bumps into Brian Bryant, ‘the most boring man in the

world’. (See Dan and Diana Danby in Ever

Decreasing Circles: character names with built-in echoes are Esmonde and

Larbey shorthand for ‘boring’.) The pair are spectacularly mismatched.

Ralph is

an appalling, cocky,

oily, boorish, charmless know-it-all and self-proclaimed ‘lone wolf’.

RALPH: You put any

door in front of my knuckles and I’ll knock on it, whether it wants to be

knocked on or not.

Brian is nervous, divorced, well

meaning, gutless and an outright passenger, musclebound by minutiae.

BRIAN: Take me, for

example: I count. Railings, stairs, bricks and so forth. Well, that’s not really

right, is it?

Both have moustaches. Both are on

their way to Spain. Both are clearly bachelors. And, as will become evident,

both are lonely.

Brian is immediately impressed by

Ralph, who (unlike him) can get the barman’s attention at a stroke (see Paul

Ryman at The Egremont Club – ‘Steward!’), and he hesitantly follows Ralph’s

lead in being markedly relaxed about boarding the plane.

RALPH: I don’t scrum,

I don’t jostle, I don’t race. I stroll. I’d sooner miss

a plane my way than catch it your way.

As a result, they do miss their

flight, arrive at their Costa del Sol hotel nine hours late and find themselves

having to share a (non-guest) room together. So is this a holiday sitcom, like Duty Free or Benidorm? To begin with, yes.

Ralph and

Brian are well written characters. But they are also, perhaps, works in

progress. Ralph has a lot in common with Martin.

Don’t quote

Shakespeare at me, Brian. Particularly when he’s in one of his cockier moods.

Look, I’m not being

old-fashioned about timekeeping. I’m just saying it’s your fault.

Brian, am I allowed to get to my crux?

I am a difficult sort of chap to get on one postcard.

I don’t like satire, Brian. Doesn’t ring bells with me.

Would you kindly put

all these little birds in your head into their respective cages and listen to

what I’m saying?

Nail on the head, Brian. Nail on the head.

And some (though far fewer) of Brian’s lines could have been Howard’s.

I should be home in

time for Nationwide.

I, personally, am my

weakest point.

That’s why I don’t

talk about myself. I’m not vital.

Everything I deal with

is totally useless.

Together, Ralph and Brian contain

the seeds of Martin and Howard’s double act.

RALPH: Look, Brian, I

am trying to scull here. Would you kindly stop dragging the anchor in the

water?

BRIAN: Sculls don’t

have anchors.

RALPH: All right,

Brian, all right. What’s the matter? Have you gone mad? Are you having a spasm

or something?

BRIAN: Well, you did

ask.

RALPH: Oh yes. He

asked. Ralph asked. And he got, didn’t he? The old death by a thousand cuts,

eh?

Ralph is irritated by Brian’s

little habits.

RALPH: The one that

comes at the top of my list is when you say, every single day that we are out

in the country, ‘Hello, hello: first cow of the day.’

BRIAN: Oh, well, I can

explain that. It’s connected with Swiss roll.

This is very typically Esmonde

and Larbey. Compare:

ANN: Hilda, why do you

call your spare room ‘The Polly Wolly Doodle Room’?

HILDA: Because of the

gramophone record.

But the big difference between

Ralph and Martin is that Ralph is, by any measure, impossible to like. Tom Good

is remembered with affection, and he’s unbearable. Ralph is awful – for solid,

comic reasons – but something drives a wedge between the character and the

audience. What?

There is a virus in TV comedy

that occasionally flares up, and it comes in the form of the note (to writers)

that the character must be likeable.

This is horseshit.

Tom Good is a bully. Basil Fawlty

is a snob. David Brent is a twat. Edina and Patsy are monsters. Brian Potter is

a martinet. Literally everyone in Spaced,

Girls and The Young Ones is a

bellend. But they’re all VERY FUNNY. ‘Like that. All in capitals,’ to quote

Georgette Heyer. And that gets the audience past the characters’ shortcomings. Likeable

isn’t necessary: they need to be sympathetic.

The viewer can sympathise with Basil’s snobbery: running a small hotel must be

like nursing a never-ending stream of picky infants, each with its own demands

and sore points.

But in The Other One, something didn’t land. Bob Larbey spotted something

was up at the first recording in December 1976:

You could feel the

studio audience recoil when Richard came forward with the moustache and the

smarmy kind of look about him. And the look said, ‘No. That’s not Our Richard.’

‘Not our Richard?’ Briers could

play unlikeable (Tom, Martin) with enormous charm. Here, Ralph is characterised

by his total lack of charm. He’s sexist, twitchy, selfish, egotistical,

meretricious, brutish, a coward and an inveterate liar. A toxic blend of

Martin’s twitch and Paul’s Teflon coating.

Brian (Michael Gambon), on the

other hand, is solicitous, gauche, proper, credulous, foolish, awkward and – also

– a coward.

Gambon’s background was in

theatre, and he was relatively unknown to TV in 1977. When he came into his

own, most notably as writer/victim Philip Marlow in Dennis Potter’s peerless The Singing Detective, it became clear

that he was an actor of astonishing chops. But in The Other One, he’s a lot less sure of himself in front of the

camera. He even fluffs his lines, quite noticeably.

Was the casting upside down? It’s

tempting to flip the actors, and imagine Gambon as an irritating

medallion-chested know-it-all with brilliantined hair and Briers as his faffing

acolyte. That might work: Gambon with his anatine tenor, Briers with his

desperation to please. But it’s simplistic.

The problem isn’t so much that

one of the two leads isn’t likeable, but that he doesn’t meet enough

resistance. There’s no counterpoint. There’s no Paul Ryman. The Other One clearly has Butch Cassidy And The Sundance Kid (aim

high – why not?) in its sights: what might now be termed a ‘road trip’ or

‘buddy’ story. But these are very fussy buddies. Resistance, had it been there,

may have fostered sympathy.

The writers even seem at pains,

in the scripts, to shore up ‘these two pariahs’. Typically, Esmonde and Larbey

wrote short stage directions. Their typical half-hour amounts to around 50

pages. The first script of The Other One

runs to a lardy 77 pages. It includes lots of what might be read as justification.

Brian ‘feels guilty,’ ‘is used to

being unnoticed,’ ‘is obviously wearing his best Hepworth’s suit,’ ‘tenses like

a greyhound in the traps,’ and ‘accepts this as his usual fate’. Ralph ‘smiles

patronizingly,’ ‘makes Brian do the hard work by volunteering nothing,’

‘chuckles a “thereby hangs a tale” chuckle,’ ‘preens in his innocence’ and

‘doesn’t have the faintest idea what’s going on, but compensates by doing a

running commentary’.

Perhaps the other significant

weakness of The Other One is its

overall story arc. The trouble with holiday sitcoms is that they rely on a cow of

a lot of suspension of disbelief – the audience has to deliberately avoid

questions like ‘why are these people still here?’ or ‘do they always come to

the same place?’ or ‘when are they going home?’ Esmonde and Larbey tackled that:

in the fifth episode of the first series, Ralph and Brian go home.

Episode six opens, and the title

sequence has changed. The sunglasses, cocktail and cigarilloed ashtray in the

opening cameos have been replaced with two briefcases – Ralph’s smart 1970s

aluminium attaché, and Brian’s battered old leather Wexford. Back to life.

(This is noteworthy. Sitcoms that

change their ‘sit’ are rare. It’s difficult to pull off. And it doesn’t quite

succeed here. The pair go from holiday pals to work colleagues, on the road,

repping together. It leaves a credibility itch in the audience’s nerve endings,

which doesn’t help.)

The remaining eight episodes see

the pair travelling around the west country in Ralph’s crimson Ford Capri trying

to sell packaging.

In Ever Decreasing Circles, the writers were prompted to explain why someone

as lovely as Ann (Penelope Wilton) married a skyscraping buffoon like Martin.

They addressed this in the second series.

ANN: When I first met Martin, quite frankly I was a

bit of a mess. I’d picked the wrong bloke, and the wrong job. Left both. I

wasn’t really coping with anything. And then suddenly there was Martin who

said, “Don’t try to cope. Leave it all to me.” So I did. He brought back some

order into my life – some security. And he was always kind. He drives me mad

sometimes, but I love him.

In The Other One, Esmonde and Larbey went to greater dramatic lengths

to apologise for Ralph. Why is he single? Was he never tempted to get hitched?

RALPH: Married? No.

Only once. I was on time all right, standing there like a lemon with a rose in

my buttonhole, making jokes about the bride always being late. She wasn’t late.

She was on the Dover ferry with my brother.

This is a moment of candour and

possibility. The awful mask slips, revealing the human beyond. A chink of

redemption. Yet, in the next scene, the following morning, Ralph is back to

usual dreadful self. Reset. A dead end.

The canniest decision Esmonde and

Larbey made (possibly in their whole career) was in the early execution of The Good Life. They had their

forty-year-old central character and his wife espouse self-efficiency, Rotovating

their garden to muddy hell; and they had the upper-middle neighbours (the

Leadbeatters – ‘better’ versus ‘good’) looking down their sitcom noses at the

Goods. Then they threw in a masterstroke: what

if these two couples like each other? Wallop.

Putting animosity to one side

left them with rich characterisations and acres of canvas. In Ever Decreasing Circles, Paul was the

nice enemy. In The Other One, the two

characters were cross with each other. They had stand-up rows. Ralph bullied

and took advantage of Brian. That seems, if there were one, to have been a

mistake.

Was The Other One, then, ‘a flop,’ as Richard

Briers called it, and ‘a glorious failure,’ as Bob Larbey said? It wasn’t the radiant

success that its neighbour series were. (There were nearly others too: Now And Then, commissioned by the BBC in

spring 1980 but which John Howard Davies nixed and eventually appeared on ITV three

years later, and Arthur’s Kingdom,

seven episodes of which were ordered in October 1979 but which didn’t happen –

why and what it was remain unclear.)

The Other One was, though,

a stepping-stone. It had the bones of Martin Bryce and Paul Ryman in it, but unfortunately

it also contained the bile of Ralph and the shrivelled balls of Brian. (The

series was originally titled Ralph And

Brian – is it too much to read a ‘R&B’ reference into this? Probably.) The

show is vinegary, and lacks much of the writers’ typical warmth.

Usually,

Esmonde and Larbey deployed ghastliness in careful measure. In The Other One, they put it front and

centre, and built an entire series around it. Esmonde and Larbey’s work tends

to glow with charm. Here, they tried something else. And not all experiments

yield success.

It’s

hardly surprising that two male writers wrote a lot of male double acts (Ben

and Walter in You’re Only Old Once,

Jacko and Eric in Brush Strokes,

Harry and Dennis in Hope It Rains)

but it is unusual for one of Esmonde and Larbey’s to have backfired.

However,

writers are proficient recyclers, and Ralph Tanner had one more (wholly

successful) outing – in the third series of Ever

Decreasing Circles, as swaggering creep Rex Tynan (played with oiky unction

by Peter Blake of Kirk St Moritz fame).

Rex T (a

dinosaur, as his name suggests) doesn’t just share his initials with Ralph

Tanner. He is also a rep. He’s also a womaniser. He also drives a red Ford

Capri. And he is a liar. He hoodwinks Martin into thinking that he has been

unfaithful to Ann on a two-day business trip to Bruges. Rex Tynan is Ralph Tanner.

What Ever Decreasing Circles got right –

sidelining a horrible character and confining him to one episode (two, if you

count Rex’s off-stage appearance as the man who stamps ‘CONFIDENTIAL’ all over

Martin’s face at the Christmas party) – The

Other One arguably got wrong.

Rex gets

punched on the nose at the end of his story. Ralph’s finale is something quite definitely

else. The closing scenes of The Other One

are a bizarre, awkward cadence in which the writers bolt headlong for the fire

exit: the lead characters get into Ralph’s car and drive off. They actually drive off together into the

future. It’s hella odd. It is an example (a bit like the slightly overstaged

finale of Ever Decreasing Circles) of

an ending being all confection and no logic. Ralph and Brian haven’t been in

love, as far as we the audience can tell, at any point: nor do they need each

other. These two lonely men have found each other and bonded, though that bond

is brittle and insubstantial and goes nowhere except into the distance. What is

set up doesn’t pay off. It is an ending, yes: but adding Shave And A Haircut (Two

Bits) to the end of Mozart’s Requiem is an ending, and adding ‘and they all

lived happily ever after’ to Animal Farm is

an ending. It just isn’t the the right one.

The

likeable horror and the significant shadow are characters that the writers had

fun with more than once, in varying shades of subtlety. Their best work was a

blend of cuddle and needle. In The Other

One, there may have been rather too much needle.

Pints this time to Ian Greaves and James Cary, for words of wisdom. Grats, amigos.

Sunday, 14 June 2015

Lots Of Dots...

How writers write is seldom explored. There are good

reasons: it’s not easily discussed, and it’s not very interesting. You might as

well ask how sneezers sneeze or accountants account. It’s largely instinct

(intangible) and craft (tangible, but prone to prescription). A writer, on her

or his own, is a brain in a jar, generating and shaping and tipping out and

re-shaping ideas quite privately. How that person writes is so internalised

that the process is almost beyond description, and likely way beyond any

entertaining or meaningful conversation.

But that answer doesn’t allow for how a twosome operates.

Writing partnerships are relationships; and relationships have

dynamics, compromises, competing urges, blazing rows and moments of love.

That’s more like it. Those elements are the makings of a story.

John Esmonde and Bob Larbey met each other at the Henry Thornton

School in Clapham. Bob was two years older than John, but they shared a sense

of humour and a love of football (later to pay off in their uncharacteristic

pancake of a series, Feet First). After

National Service (later to pay off in the far more successful Get Some In!), they met up, at the old boys’

club, playing football together (later to pay off in… well, read on) and making

themselves – and others – laugh.

Being friends before we became partners was, I'm sure, a great

bonus. The success we enjoyed together is partly due to having known each other

for so long. Having been friends first made writing more of a shared pleasure.

At the time, John was working as a technical journalist, and Bob was

employed by a printing block maker. Neither found it fulfilling.

Office jobs did nothing for us and not a lot for our employers, so –

rather like Tom Good – we looked for a way out. We chose comedy writing instead

of self-sufficiency and used all our spare time sending stuff here, there and

everywhere. All of it was turned down, of course, but we stuck with it and,

some four years, later sold our first comedy sketch to BBC radio.

Thrown these crumbs of success, they started writing more often –

initially in the evenings, while maintaining their day jobs, until they started

to fall asleep at work and took the plunge to become full-time writers.

Writing partnerships tend to work to one of two methods: one is the ‘type-and-pace’

method (Cleese and Chapman, Mitchell and Webb) where one notes it all down

while the other paces the room, and the ‘write-and-swap’ method (Fry and

Laurie, Bain and Armstrong) where both write separately, then swap material and

rewrite each other’s work. Both styles require having first brainstormed the

idea thoroughly. Esmonde and Larbey were of the former.

When we were creating a script, we’d take it in turns to do the

writing. We

used to write longhand, as opposed to typing the script straight away, which we

always found distracting.

Their

surroundings were deliberately unglamorous.

We rented a series of disgusting little offices and just used to go

to work – sit in the same room, talk a lot, drink a lot of coffee.

Their

first disgusting little office was at 47 West Street, Dorking, mid-way between

their homes. Later, they moved to a little office above a greengrocer’s in

Billingshurst – where Ever Decreasing

Circles was written and (perhaps uncoincidentally) the exteriors were

filmed. It was also disgusting.

It wasn’t long before there was fag-ash, cups that hadn’t been

washed for days and bits of paper everywhere. Not many people came to our

office, but those who did used to say, ‘Oh my God, how can you work in filth

like this?’

They started with the bit they found hardest: plot structure.

John and I always write a very detailed story-line before starting

on the script. By that time we’ve a pretty good idea of what’s going to happen.

Then they routined the scenes, playing the parts themselves ‘very

badly, but to our ears they were perfect’.

We’d get into a stream of improvised dialogue and afterwards try and

remember what it was that had made us laugh, then write it down. That's the

hardest part.

Many writers stick to this rule. The simplicity of it is very

appealing: use Take One. That’s the line or idea which came out unrefined, before

being overthought or overstudied or over-written. What was the exact wording

that made you both laugh? It’s probably right. Sometimes, it can be something

apparently innocuous. In the last (longer than usual) episode of Ever Decreasing Circles, Martin’s

employer, Mole Valley Valves, merges with Lee Valley Valves, and relocates. Martin

is being forced out of The Close: his basic nightmare. Esmonde and Larbey had previously

made great play of Martin and Ann’s night in Kidderminster (indeed, ‘Kidderminster,’

in the dialogue, comes to stand for ‘passion’), but now the writers needed a

place name that smacked squarely of alien waters. A by-word for ‘not The

Close’. Something cold, difficult, new – and funny. In the writing session,

this happened.

How about, ‘I’ve

just had Oswestry chucked in my face’?

This was, they decided, perfect. Oswestry, with its combination of far-away-ness

and audible curlicue (comedy is music; it has to sound right: ‘Discuss the

contention that Cleopatra had the body of a roll-top desk and the mind of a

duck’ – thank you, Richard Sparks), hit the mark.

We both knew immediately that Oswestry was just right. I mean, there

are times when Kilburn can fit the bill, and others when it just has to be

Thames Ditton. Not only did Oswestry have the right ring to it but, being

almost in Wales, it must have seemed to suburban Martin like East Africa.

This kind of detail appealed to Esmonde and Larbey. One Ever Decreasing Circles (the Gasthaus

Glockenspiel episode, explored in the previous post as the possible bandage

across a story wound) starts with a lengthy scene about a missing three-eighths

grub screw. That's not funny per se

but, coming from Martin Bryce’s mouth, it’s a hatch-down moment of terrible

importance: his invaluable three-eighths grub screw lost, he needs to find it.

Nothing can stand in his way. Detail. Detail.

Detail is the arena of quotable comedy. (See I’m Alan Partridge: ‘I gorged on Toblerone and drove to Dundee in

my bare feet.’) Esmonde explained as much.

People ask where we get our dialogue from, but they

don’t realise it’s all around you. Like a feller the other day in a shop: ‘I

have here a statistic,’ he says, ‘viz,’ he says, ‘that there are more people in

Italy kicked to death by donkeys than what die in air crashes.’ With jokes it’s

either win or lose. But, if you write characterful dialogue there’s another

level of funniness. We don’t think that people are innately witty when they

talk. We prefer a laugh from the way a character says, ‘Well…’

Bob Larbey backed this up, with a very fine example.

Once, working on The Good Life, we thought we would see if we could get

laughs from a totally unfunny script. We wrote a whole page with nothing but

‘Good morning’ on it.

He slightly misremembered this, but it is a magnificent scene. ‘The Wind-Break War,’ arguably the finest

episode of The Good Life, sees the

Goods fighting the Leadbeatters quite needlessly over the positioning of a tall

fence that accidentally casts a shadow over the Goods’ soft fruit. There is a

fight, and a lot of wonderful passive aggression, and the Goods move their

entire crop to defeat what they see as the Leadbeatters’ sabotage manoeuvre. Yet

it’s nothing of the sort. It is a misunderstanding. And, when that’s revealed,

the couples revert to embarrassment.

That is (and it’s from the one published Good Life script) a minute of dialogue. Nothing, on the page,

distinguishes it from small talk. Yet the context, timing and (crucially)

performance of the scene make it as good as anything Esmonde and Larbey wrote. Somehow

it advances everyone in it, without needing any exposition on the page. It

does nothing and does everything. The characters are so well worked out that

the scene can be set going, and simply roll to the front and collect its

laughs. It’s close to perfection, but good luck justifying that.

‘Looking at our scripts… Just lots of dots…’

The Good Life was, like that snippet, an idea that had travelled far enough from

its inspiration to become a functioning organism.

The Good Life never set out on a

theme of self-sufficiency. We started with the premise of somebody reaching his fortieth

birthday. People think of it as one of those milestone ages, the ‘Oh, God, what

have I done with my life? What do I do about it?’ John and I wanted to write about a man who was fed

up with his job and fed up with himself. He could have become a lorry driver. [In the original draft, he was going to build a yacht and sail

around the world.] But we added the

self-sufficiency, which seemed a good idea. When we’d got him in our minds, it

was he who decided what he wanted to

become. The character takes over.

Plenty of sitcom characters come from real life. Famously, Basil

Fawlty was found by John Cleese in Donald Sinclair, the insufferable hotelier

of The Gleneagles Torquay. Just so Martin Bryce. In contrast to the oft-told

story of the anonymous ‘referee on Clapham Common’ the writers repeated to the

cameras, in conversation with Richard Webber, author of A Celebration Of The Good Life, John Esmonde offered this more

revealing progenitor.

Bob and I used to play old boys’ football, and we had regular

meetings to talk about subs, match fixtures, things like that. This [one] chap

would arrive with a briefcase and give a dissertation on how to take a penalty.

Now, think of that happening in someone’s front room. [He] was certainly no

lithe athletic type, being unbelievably English in his fairness but, at the

same time, really frustrating. He was always painfully keen. I remember one

week we were playing a match and didn’t have a referee, so he decided that he’d

be the ref and play as well. As you can imagine, that’s quite difficult. He

even scored – after which he apologised to everyone on the other side.

The writers recognised the potential for comedy in their erstwhile

colleague, and ran it past their bench test.

I have only two criteria in trying to think up a new idea: will the

idea stay funny for more than a few episodes and do I think it's funny in the

first place?

Yes and yes. So down to work.

When you first create characters, you think a lot about them of

course, but you never know everything about them, so when you have an idea for

a story – say, a dance – you have to work out whether your characters like to

dance and, if so, how they dance. I don't suppose you'd covered that

eventuality when you first invented them.

Martin, of course, is a man with a colossal catalogue of issues. In

one episode, he tells Ann, ‘I’m writing a letter to The Times.’ ‘What about?’

she asks. His reply is both ludicrous and bang on: ‘Everything’.

Martin was terribly tortured. He had so many little bees and bugs in

him. His hang-ups were amusing, yet totally realistic, because I’m sure there

are plenty of people who can’t stand telephone wires getting tangled up,

road-sweepers leaving cigarette butts behind, molehills, awkward-looking odd

numbers – just some of the aspects of life that irked Martin terribly. [He]

could see the perfect world on the horizon, but never quite reached it.

Once Esmonde and Larbey had established their protagonist, they went

to work on his opposite number.

We got the idea of someone who wanted life to be perfect, who wanted

life to fall into place around him, to the point of being neurotic. Then we

asked ourselves, ‘What would rock that particular boat?’ The answer was a

nearby Mr Perfect who breezed through life getting everything right.

A good test of character is always to ask, ‘What’s the worst thing

you could say to this person?’ The answer, in Martin’s case, happens very early

on – in the second episode of the first series.

PAUL: Isn’t it time we started to ease the world off old Atlas’s

shoulders?

HOWARD (RISES): You’re absolutely right.

MARTIN SHOWS FEAR.

HOWARD: It’s about time we pitched in and did some of the work

ourselves.

PAUL: Some? What good will some do? This man needs a total break

from all of it.

HOWARD: That’s it! I formally suggest we take every job that Martin

does for every club and every society and share them out among ourselves.

MARTIN’S SMALL ‘NO’ IS LOST IN A CHORUS OF ‘HEAR HEARS’.

Cutting Martin’s balls off – as happens here – by saying, ‘I’ll do

it: you sit down’ is the most ruinous thing that has ever happened to him. Showing

this worst case scenario so early on in the series serves to strengthen the

character. Esmonde and Larbey knew this: they were at the top of their game

writing Ever Decreasing Circles.

Richard Briers described them at the time, without undue exaggeration, as ‘the

best in the trade’.

They were also strict. If one of them disagreed strongly about

something in a script, it was nixed. Likewise, they weren’t unafraid of killing

their darlings if they didn’t stand up to scrutiny.

You can think of a funny line and

then ask yourself whether so-and-so would ever say such a thing. If he

wouldn’t, you have to toss it away.

Briers was a gift: it has been said many times before, but it

deserves underlining. A brilliant piece of music played by an average musician is

too readily an average piece of music. But hear it played with flair and guts,

by a brilliant musician, and you’re gifted the thing the composer intended.

Likewise comedy. To have something performed, semiquaver perfect, by an actor,

is an unalloyed joy.

Seeing it is

quite exciting. Sometimes we laugh.

Richard Briers was an expert at making an unlikeable character

likeable. Tom Good is, in all truth, a bit of a shit. He ignores his wife for

three years. Martin Bryce is impossible to live with: Richard Briers makes it

possible. Esmonde and Larbey wanted Briers from the off, because they reasoned

that he was probably the only actor who could make Martin in any way loveable.

They were right.

And there were at least two good reasons the writers kept their lead

actor in mind. Firstly, if, as the writer, you can hear the character’s voice,

it becomes much easier to write them, and they start to sound real. Half your

job is in the bag.

Secondly – and this is the kicker – Ever Decreasing Circles (nearly called One Man’s Close, Close Connections and The Close Friend) might adhere to the (then) conventions of studio

sitcom (four sets, four minutes of film per ep) but the the show isn’t set in

The Close, it’s set in Martin. The

‘sit’ bit of the sitcom is its principal character himself.

A lot of series are about what people do… what they try to get done.

This was about the inside of his head more than anything else. Things like

colour coding, counting, clean shoes: everything in its place and a place for

everything.

The show set in someone’s head wasn’t new then (see the truly

amazing – and enough cannot be said about it – The Strange World Of Gurney Slade for an earlier example) and has

been done since (the lovely chamber piece Marion

And Geoff, for instance). But Ever

Decreasing Circles externalised that idea, because the writers spread the

world inside the man’s head into the world outside his head. Howard and Hilda

are the best neighbours Martin Bryce could wish for; Paul Ryman the worst. Martin has angels and devils, and they live either side of him: on each

shoulder, if you like. That such a simple idea could easily slip into

caricature is obvious; that it didn’t is testament to the writing.

The last decision a writer makes is when to stop. Esmonde and Larbey

halted after four series of Ever

Decreasing Circles, just as they did with The Good Life. Enough, when it seems so, is enough.

We prefer to leave the public wanting more, rather than run out of

things to say.

How did Esmonde and Larbey write? Very well.

A shipping container of

thanks is shared by Steve Arnold, for pointing me towards a rich seam of Radio

Times articles, and Richard Webber, whose book A Celebration Of The Good Life (Orion,

2000) yielded a great many quotes from Esmonde and Larbey for this piece. If

you don’t own the book, correct your error at once. It is one of a kind.

Other sources: ‘The laughter lies in the toil’ (Gordon McGill, Radio Times, 27 March 1975), Television Comedy Scripts (ed. Roy Blatchford, Longman, 1983), ‘It’s a good, busy life for Richard’ (uncredited, Radio Times, 23 January 1984), ‘The luck of the insecure actor’ (Tim Heald, Radio Times, 20 October 1984), ‘Will Jacko say “I will”?’ (Jenny Campbell, Radio Times, 26 November 1988), ‘Funny line of work’ (William Greaves, Radio Times, 23 December 1989), Biography: John Esmonde and Bob Larbey (Television Heaven, 17 February 2005), Bob Larbey interview with Robin Kelly, Writing For Performance (2005), Comedy Connections (BBC, 2006), John Esmonde’s obituary (The Times, 12 August 2008).

Other sources: ‘The laughter lies in the toil’ (Gordon McGill, Radio Times, 27 March 1975), Television Comedy Scripts (ed. Roy Blatchford, Longman, 1983), ‘It’s a good, busy life for Richard’ (uncredited, Radio Times, 23 January 1984), ‘The luck of the insecure actor’ (Tim Heald, Radio Times, 20 October 1984), ‘Will Jacko say “I will”?’ (Jenny Campbell, Radio Times, 26 November 1988), ‘Funny line of work’ (William Greaves, Radio Times, 23 December 1989), Biography: John Esmonde and Bob Larbey (Television Heaven, 17 February 2005), Bob Larbey interview with Robin Kelly, Writing For Performance (2005), Comedy Connections (BBC, 2006), John Esmonde’s obituary (The Times, 12 August 2008).

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)